Fantastical

Plants of the Western Ghats

Featuring plants native to the rainforests of India’s Western Ghats—from carnivores to parasites to flowers that stink of rotting flesh—this exhibit reveals a fascinating kingdom of irreplaceable value, often hidden in plain sight.

Read with:

Hidden Kingdom: Fantastical Plants of the Western Ghats

Spiral Ceropegia

Info

| Common name | Spiral ceropegia |

|---|---|

| Scientific name | Ceropegia spiralis |

| Family | Apocynaceae |

| Local names | Amruthaanjanagadde (Kannada) Pilachi Khantudi (Marathi) |

| Distribution | Endemic to southern peninsular India |

| What to look for | A small herb of size 20–30 cm with flowers about the length of a finger |

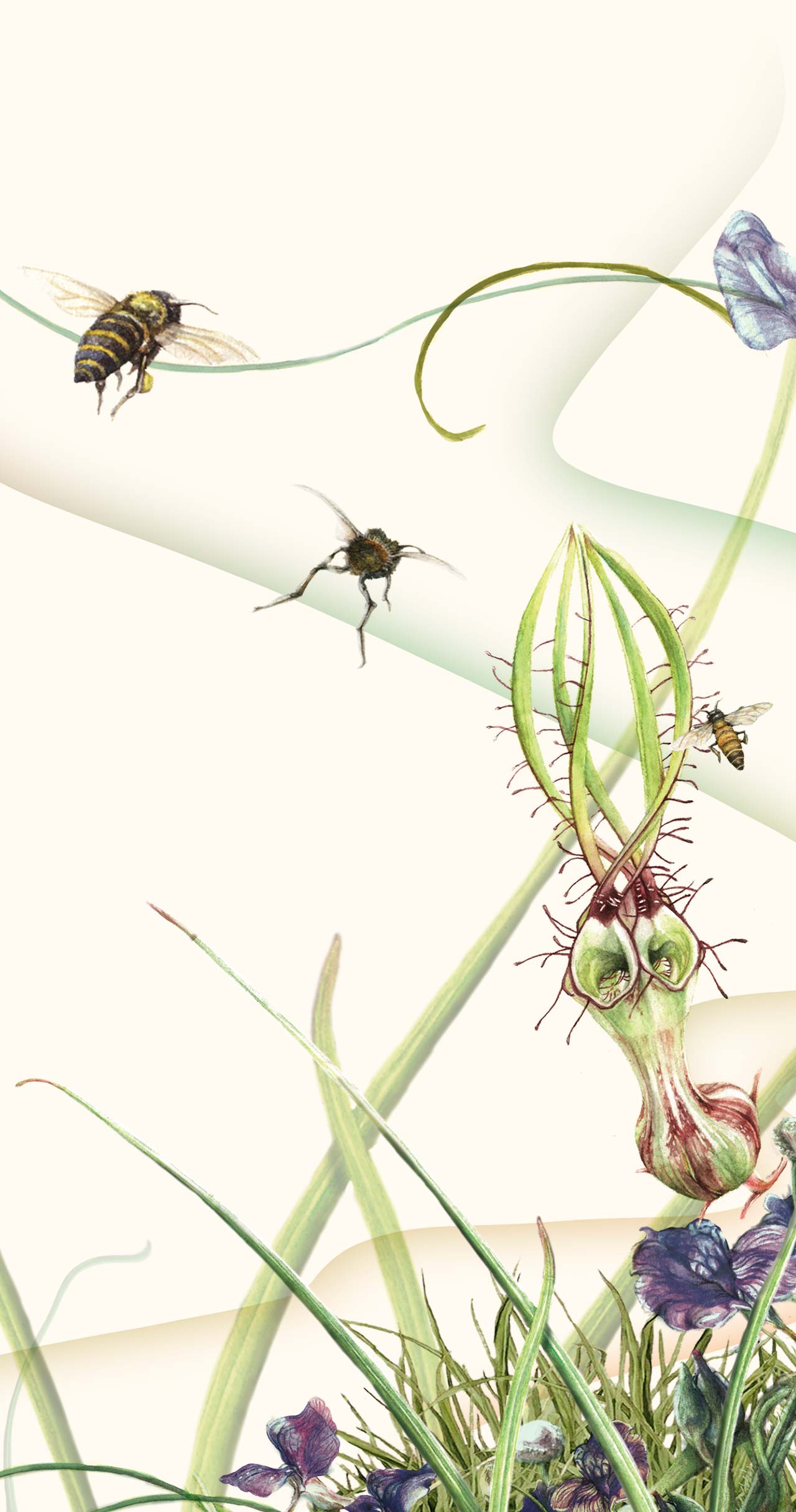

Ceropegia are insect-trapping (but non-carnivorous) plants found in Asia, Africa, Australia, and the Canary and Pacific Islands.

-

200

ceropegia species across the world

-

28

ceropegia species found only in India’s southern peninsular

Various kinds of ceropegia flowers have the same general construction, but with an array of different colours and shapes. This general shape helps to attract and temporarily trap its main pollinating agents… flies!

Study these three photographs together: each start with a cage-like structure at the top (which in fact are the flowers’ petals) through which the fly enters. Next comes a long, tube-like neck—once the fly falls down the tube, it’s difficult for it to climb back out. Instead, it is trapped for a while in the bulb of the flower, where pollen becomes attached to its body. Finally, the petals turn downward, allowing the fly to escape, carrying pollen along with it to the next flower.

Myristica Swamps

Info

| Common name | Magnificent nutmeg |

|---|---|

| Scientific name | Myristica fatua var. magnifica |

| Family | Myristicaceae |

| Local names | Ramapatre (Kannada) Kottapannu, Kothapayin, Churapayin, Kotthapanu (Malayalam) |

| Distribution | Endemic to the Myristica swamps |

| What to look for | A tree of up to 20m height with stilt roots sprouting from its trunk |

A swamp is an area of land that is permanently filled with water. They are often named after the trees that grow in them—Myristica swamps are named after the tree family (Myristicaceae) that is most abundant here.

Across the world, there are two main kinds of swamps: saltwater, which form on tropical coastlines, and freshwater which form inland, around lakes and streams. Swamps are therefore neither completely land nor water, but transition zones between the two.

Myristica swamps are freshwater swamps. It is believed that, at one time, they would have formed a network along the water courses through the primaeval forests of the Western Ghats. Since then, much has been converted for agriculture or irrigation projects, and the remaining swamp land can be found in smaller patches.

It is difficult for plants to grow in water-logged conditions and so they have evolved various adaptations such as aerial roots. In these pictures, and in your book, you can see the stilt roots of the Magnificent nutmeg (Myristica fatua) and the knee roots of the Kanara nutmeg (Gymnacranthera canarica). Such roots provide additional support to the plant, while also allowing the roots to breathe.

The Myristica swamps have a great number of endemic species, both flora and fauna. The lion-tailed macaque, the Myristica sapphire damselfly, several fish and amphibians are only found in this habitat. Swamps are also especially important for environmental stability. During times of heavy rain, they naturally help to control floods by storing excess water. Additionally, in swampy areas, water is able to slowly seep into the soil, thereby replenishing our groundwater supply. The loss of swamp lands contribute to flooding and soil erosion.

Info

| Common name | Kanara nutmeg |

|---|---|

| Scientific name | Gymnacranthera canarica |

| Family | Myristicaceae |

| Local names | Pindi (Kannada) Pintikkaya, Udaipami, Undaipanu, Undapayin (Malayalam) |

| Distribution | Endemic to the Myristica swamps |

| What to look for | A tree of up to 25m height with loop-like roots popping up at its base |

Myristica species are also wild relatives of the Indonesian True nutmeg (Myristica fragrans), from which we derive the nutmeg spice we eat. Their fruit structures are very similar. Take a look at the image: it shows the inside of a magnificent nutmeg fruit, with a large seed and brightly coloured seed coating. Nutmeg spice is derived from such a seed, while the seed coating gives us mace.

Learn more

Exhibit 02: Spirit of the Forest

Black Pepper

Info

| Common name | Black pepper |

|---|---|

| Scientific name | Piper nigrum |

| Family | Piperaceae |

| Local names | Kali mirch (Hindi) Karimenasu (Kannada) Kurumulaku (Malayalam) Golmirich/Kali miri (Marathi) Kurumilagu (Tamil) |

| Distribution | Native to southern India, although now cultivated in many tropical countries |

| What to look for | A flowering vine, growing up to 8m high on trees or poles |

Historically, pepper has been one of the most sought after spices in the world largely due to its medicinal properties. Just how sought after, you ask? In Europe in the Middle Ages, it was an incentive for Vasco da Gama and the Portuguese to seek a sea route to India! It was sometimes used as a sort of currency due to its high value, compact size, and durability. Think about it: those are the same properties we value in money.

Black, white and green pepper are all produced from Piper nigrum fruits, but are harvested at different times and processed differently. Betel leaf (Piper betel) is also from the same genus, and a number of other wild species are also called pepper locally, and used in a similar manner. For example, Indian long pepper (Piper longum), is native to the region from Assam to Myanmar. Sichuan pepper, often used in Asian cooking, is obtained from Zanthoxylum species. In South America, Pink pepper is obtained from the Brazilian pepper tree (Schinus terebinthifolius).

Cluster Fig

Info

| Common name | Cluster fig |

|---|---|

| Scientific name | Ficus racemosa |

| Family | Moraceae |

| Local names | Goolar (Hindi) Rumadi (Kannada) Atti (Malayalam, Tamil) Umber (Marathi) |

| Distribution | Native to Australia, Indo-China and the Indian subcontinent. In India, they can be found commonly even in cities and towns |

| What to look for | These are often large trees, up to a 100 ft high, with colourful fruit growing directly from branches |

Ficus is a genus of around 850 species of trees, shrubs and vines collectively called ‘figs’. They are found natively throughout the tropics, and include some of our most beloved Indian trees such as the peepal (Ficus religiosa) and the banyan (Ficus benghalensis). It also includes the fig fruit that humans love to eat—Ficus carica, native to the Middle East and Western Asia. In your book, you can see the cluster fig tree (Ficus racemosa), whose most distinctive feature is that its fruit grow abundantly in clusters directly from the tree’s trunk.

Fig trees form a very important part of jungle ecosystems because they fruit multiple times a year, which means that some kind of fig fruit should be available all year round—even in seasons when most other trees aren’t in fruit. So many birds, bats and primates rely on fig fruit for their sustenance that they are known as a ‘keystone’ resource in the jungle. Like the keystone of a bridge, if figs disappear, all else could come crashing down!

Figs are also fascinating for their complex pollination strategy. Interestingly, fig flowers are located inside the fig fruit, known as a ‘syconium’. In order to access these flowers, the pollinator has to enter the fruit through a tiny hole called an ‘ostiole’. Figs have therefore evolved a special relationship with fig wasps: the mother wasp lays her eggs safely among the fig flowers inside the syconium. When the baby wasps are born, the males dig little escape tunnels in the fruit wall for the females. The males then die and dissolve within the fruit! Meanwhile, the female wasps, carrying the fig’s pollen with them, fly off to other syconia in search of a place to lay their eggs—thereby completing the pollination cycle. This relationship began more than 80 million years ago, and now nearly every species of fig has its own partner wasp species! In fact, Ficus species likely produce fruit all year round in order to ensure its pollinator wasps survive.

Strangler Fig

Info

| Family | Moraceae |

|---|

-

850

species of trees, shrubs and vines collectively called ‘figs’ comprise the Ficus genus

The term ‘strangler fig’ is applied to a particular growth pattern displayed by many species of the Ficus genus. They are found natively throughout the tropics and include some of our most beloved Indian trees such as the peepal (Ficus religiosa) and the banyan (Ficus benghalensis)—both of which display strangling behaviour.

What in a whodunnit-murder-mystery is that? Well, it is essentially a growth method developed to get a leg up on the competition. The rainforest floor can be a difficult place for young seedlings to develop, as very little light filters down through thick overhead canopies. There is also a great deal of competition for water and nutrients with other plants. So unlike most other plants, strangler figs start their lives off as epiphytes on the branches of another fully grown tree. Their seeds are usually dispersed by birds, who drop them atop an existing tree, from where the fig begins to germinate.

First, the strangler sends out many thin roots that crawl down the trunk of the host tree toward the ground, or dangle as aerial roots. Eventually, these roots hit the ground, dig in, and begin to compete with the host tree for resources. As the roots grow, they thicken and form a lattice around the trunk of the host, while putting out a thick canopy of leaves that overshadow the host, robbing it of sunlight. Eventually, the host dies due to loss of sunlight and competition for nutrients, and the strangler stands on its own as a hollow cylinder of roots.

Despite their deadly reputation, stranglers are important members of rainforest ecosystems. Besides providing fruit for many species, their hollowed-out trunks provide homes for many rodents, invertebrates, bats, birds, reptiles and amphibians.

Basket Fern

Info

| Common name | Oakleaf fern |

|---|---|

| Scientific name | Drynaria quercifolia / Aglaomorpha quercifolia |

| Family | Polypodiaceae |

| Local names | Hanumana hastha, Hanumana paada (Kannada) Matilpanna, Panna-kelengo-maravara, Pannakilhannumaravala, Welli-panna-kelengu-maravara (Malayalam) Ashvakatri, Basingh (Marathi) Pannakkilannu (Malayalam, Tamil) |

| Distribution | Asia, Papua New Guinea, Fiji, Polynesia and tropical Australia |

| What to look for | A commonly seen epiphyte thickly covering the branches of old trees, especially along roadsides |

Species belonging to the genus Aglaomorpha are commonly called ‘basket ferns’. They are either epiphytes (plants that grow on other plants without being parasites) or lithophytes (plants that grow on rocks). The oakleaf fern is a particular kind of epiphytic basket fern. Basket ferns are characterised by two kinds of leaves: short, sterile ‘nest’ leaves and long ‘foliage’ leaves. The nest leaves start off green, but eventually turn brown and die—but rather than shed them, the plant keeps them on in the form of a sort of basket at the plant’s base. This basket is used to collect litter and organic debris—falling leaves, flowers, twigs, animal droppings and more—which decompose into humus, providing the plants with nutrients they would otherwise not have received from being suspended above ground. They are plants that make their own compost, thereby giving themselves access to a private supply of nutrients! They also host a whole lot of other organisms in their baskets. Some of these inhabitants aid the plant by accelerating decomposition, but others compete for nutrients with the host plant. Oakleaf ferns are so called because their nest leaves resemble the leaves of an oak tree.

Besides the nest leaves, oakleaf ferns also have long, green foliage leaves, which bear ‘spores’ on their underside. Ferns use these spores to reproduce—unlike most other plants which reproduce through flowers and seeds. Ferns, in fact, constitute an ancient group of plants, some as old as the Carboniferous Period (which began about 350 million years ago). Their type of life cycle, dependent upon spores for dispersal, appeared long before the seed-plant life cycle that we are so familiar with today. Did you know that ferns flourished in the age of dinosaurs before they were later overtaken by the rise of flowering plants?

Ghost Orchid

Info

| Common name | Ghost orchid |

|---|---|

| Scientific name | Epipogium roseum |

| Family | Orchidaceae |

| Distribution | Tropical Africa, Asia, Southeast Asia, New Guinea, Australia and some Pacific Islands |

| What to look for | A leafless stem up to 80 cm tall with numerous flowers |

The Orchidaceae are a diverse and widespread family of flowering plants, known for their attractive blooms. Along with Asteraceae, they are one of the largest families of flowering plants in the world with almost 30,000 accepted species. About 1200 species can be found in India, of which 275 are found in the Western Ghats.

Orchids have an interesting way of feeding themselves. Unlike other plants, orchid seeds have virtually no reserve energy to support the germinating plant. So they strike up a mutually beneficial relationship with a ‘fungal symbiont’. Basically, fungi that live in the orchids’ roots help the orchid absorb nutrients from the soil, in return for carbon fixed through photosynthesis. Once the orchid matures, it is usually capable of supporting itself.

Ghost orchids, however, take things a step further. They grow on dark forest floors, where sunlight is scant. They have completely lost their ability to photosynthesise, and rely totally on their symbiotic relationship with fungi. The biggest sign of this is that the plant appears almost completely white, lacking any chlorophyll or leaves. The orchids’ roots are in direct connection with the fungi, which in turn derive nutrients either from dead organic matter in the soil or from surrounding plant roots. Ghost orchids are aptly named for their deathly, lifeless appearance. Spooky!

Sundews

Info

| Common name | Tropical sundew |

|---|---|

| Scientific name | Drosera burmannii |

| Family | Droseraceae |

| Distribution | Australia, India, China, Japan, and Southeast Asia |

| What to look for | A small, compact plant, normally spanning only 2 cm, with bright, green-red leaves |

‘Sundew’ is the common name for the genus Drosera, one of the largest genera of carnivorous plants in the world. There are three species of sundews in the Western Ghats, all of which are pictured here.

Info

| Common name | Flycatcher |

|---|---|

| Scientific name | Drosera indica |

| Family | Droseraceae |

| Distribution | Asia, Australia, Africa |

| What to look for | A small herb, 5-50 cm long, with long, sticky tentacles |

Sundews are usually found in bogs, sandy banks or other mineral soils that are low in organic nitrogen and phosphorous content. They compensate for the lack of nutrients they would otherwise derive from the soil by trapping and ingesting insects—fungus gnats, ants, crickets, spiders, bloodworms, fruit flies and more. Sundews are equipped with muciliginous glands which secrete a kind of glue that captures insects that venture near. This glue resembles drops of dew, from where the plants get their name.

Info

| Common name | Shield sundew |

|---|---|

| Scientific name | Drosera peltata |

| Family | Droseraceae |

| Distribution | Australia, New Zealand, India and most of Southeast Asia |

| What to look for | A small herb, 5-50 cm long, named after the shield-like shape of its leaves |

As the trapped insect struggles, it is covered in sticky mucilage and suffocates to death. The sundew then secretes a second kind of enzyme with which it digests the insect and extracts its nutrients.

Glory Lily

Info

| Common name | Glory lily, Tiger claw |

|---|---|

| Scientific name | Gloriosa superba |

| Family | Colchicaceae |

| Local names | Bachnag, Kadyanag, Kari hari, Languli, Ulatchandal (Hindi) Agnisikhe, Karadikanninagadde, Siva-raktaballi, Siva-saktiballi (Kannada) Kithonni, Mendoni (Malayalam) Kal-lavi, Indai, Khadyanag, Vaghachabaka (Marathi) Kallappai kilangu (Tamil) |

| Distribution | Native to India, tropical Africa and Southeast Asia. Common in thickets, grasslands, hedges, bushland and open forest, where it can be seen scrambling through other shrubs. It is the national flower of Zimbabwe, and the state flower of Tamil Nadu. |

| What to look for | An herbaceous plant which climbs with the use of tendrils at the tips of its leaves |

Chemicals derived from all parts of the plant are used in traditional medicine in tropical African countries. In India, it is much used in Unani and Ayurvedic medicine. It is also used as an antidote for snake bites and scorpion stings. But in larger doses, it is very dangerous and can be—yikes—fatal!

It is planted around doors and windows to repel snakes, and in Nigeria, is even used at the tips of poison arrows. While its human uses are interesting, it should be remembered that these are, in fact, defence mechanisms for the plant to prevent herbivores from feeding on it.

Elephant Foot Yam

Info

| Common name | Elephant foot yam |

|---|---|

| Scientific name | Amorphophallus paeoniifolius |

| Family | Araceae |

| Local names | Oal, Gandira, Jangli suran, Kanda, Madana masta (Hindi) Gandira, Suvarna-gadde (Kannada) Cinapavu, Karunakarang, Kizhanna (Malayalam) Suran (Marathi) Anaittantu, Boomi sallaraikilangu, Camattilai (Tamil) |

| Distribution | Africa, South Asia, Southeast Asia and tropical Pacific Islands. In India, it is grown as a crop mostly in Bihar, West Bengal, Kerala, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra and Orissa. |

| What to look for | The flowers of the elephant foot yam are called an ‘inflorescence’ (i.e. a group or cluster of flowers arranged on a stem). Note the small, pale flowers positioned on a stem-like ‘spadix’, crowned by a large bulbous knob and encircled by a large, maroon, velvety sheath or ‘spathe’. This inflorescence can be up to 40–50 cm tall and 30–40 cm across. The tuber can weigh up to 15 kg! |

The tuber or ‘corm’ of the elephant foot yam is cooked and eaten across India. Meanwhile, its inflorescence displays a captivating strategy to attract its main pollinators: dung beetles, which like to feed on and lay their eggs in decaying and rotting matter. The inflorescence therefore mimics such rotting matter: first visually, with its purplish brownish colour and secondly, by emitting a strong, rotting meat smell. The flowers bloom only for about five days, and their odour is strongest at night. Interestingly, they also produce an intense heat of 30–45° C. The beetles soon realise the deception and move on, but the flower’s work is done. The beetles move onto the next flower, carrying pollen with them.

Neelakurinji

Info

| Common name | Mal karvy |

|---|---|

| Scientific name | Strobilanthes sessilis var. Ritche |

| Family | Acanthaceae |

| Local names | Topli karvi (Marathi) |

| Distribution | Species from the Strobilanthes genus once grew abundantly in the Shola grasslands of the Western Ghats, although now much of their habitat is occupied by plantations and dwellings. They normally grow on hill slopes where there is little or no tree forest. |

| What to look for | A tall, bushy shrub with purplish flowers |

The genus Strobilanthes has a number of species whose flowering cycles range from one to 16 years! Of these, the Neelakurinji (Strobilanthes kunthiana), which blooms once every 12 years, is probably the best known. While the drawing in your books features the Neelakurinji, the photograph here shows a related species, the Mal karvy (Strobilanthes sessilis var. Ritche), which flowers every seven years.

Plants like these that bloom after a long interval are called ‘plietesials’. Plietesial plants grow for a number of years, flower ‘gregariously’ (in unison), set seed and then die. Since such plants have only one chance to reproduce, they invest all their resources into this single event. When these plants flower in unison, they cover entire hillsides in carpets of blue, attracting pollinators like the Indian Honeybee to the feast. This way, they overwhelm any form of competition, ensuring that the pollinators only see Strobilanthes for miles round!

It is suggested that the Neelakurinji gave the Nilgiris (the ‘Blue Mountains’) their name. They are of great cultural value to people of the area, who are even known to calculate their ages by flowering cycles.

Match the following

Back to top

Back to top